“An Android crackme arose from hell. It doesn’t make prisoners”

This post details several ways of solving the level 3 of the Android crackmes released by the OWASP guys (Bernhard Mueller). To begin with, a hardened APK is provided and the main goal is to extract a hidden secret from the app.

Security mechanisms in UnCrackable Level3:

Anti-hacking techniques were implemented in the APK, principally to slow down reversers. Take a seat because now we will have to deal with all of them.

We have detected the following protections on the mobile application:

- Java anti-debugging

- Java integrity checks

- Java root checks

- Native anti-DBI (Dynamic Binary Instrumentation)

- Native anti-debugging

- Native integrity checks of the Dalvik bytecode

- Native obfuscation (only a bit of symbol stripping and the function protecting the secret)

The following security mechanisms were not found in the application though:

- Java anti-DBI

- Java obfuscation

- Native root checks

- Native integrity checks of the native code itself

Before get started:

To begin with, consider the remarks below before analyzing the APK:

- The Android phone needs to be rooted.

- Anti-instrumentation, anti-debugging, anti-tampering and anti-rooting checks are in place both at the Java and native level. We do not need to bypass all of them but extract the secret.

- The native layer is where the important code is executed. Do not be distracted with the Dalvik bytecode.

- My solutions are just a way to solve the challenge. Maybe there are better and clever solutions appearing soon.

Possibles solutions:

This challenge could be solved in so many ways. First of all, we need to know what the application does underneath. Basically, the app performs a verification with user input and a secret hidden within the application. This is done by verifying the user input against a Java and native secret that are xored with each other. The verification is done at the native level after sending the Java secret through the JNI bridge to the native library. In fact, the verification is a simple strncmp with the user input and the xor operation of the secrets. The pseudo-code of the verification is as follows: (names are given by me)

strncmp_with_xor(user_input_native, native_secret, java_secret) == 24;

Therefore, we need to extract the two secrets to determine the right user input that displays the message of success. The Java secret can be recovered very straightforward just by decompiling the APK. However, the native secret cannot be easily recovered and just statically reverse engineering the code can be rather tedious and time-consuming. The native function conceals the secret by obfuscation which makes tough a pure static reverse engineering approach. However, hooking or symbolic execution might be a way clever idea. For extracting such secrets, my initial thoughts were performing:

- static reverse engineering plus dynamic analysis by using

Frida. - static reverse engineering of the Dalvik and native code plus code emulation with

Unicorn. - static reverse engineering of the Dalvik and native code plus symbolic execution by using

angr. - patching Smali code (Dalvik) and native code to NOP out all the security checks by using

Radare2.

My Solution:

My final inclination was going for the binary instrumentation of the Android app at runtime. For that purpose, Frida was my choice. This tool is a framework that injects JavaScript to explore native apps on Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS, Android, and QNX and on top of that it is being continuously improved. What else can we ask for? Let’s use Frida then.

Toolbox: Choose your guns!

The following list illustrates different tools that could be used with the same goal. Feel free to pick the ones you prefer the most:

- Android phone or emulator to run the crackme APK.

- Reverse-engineering:

- Disassemblers:

Radare2from git.IDA Pro.

- Decompilers:

- Native code:

Hexrays.Retdec.Snowman.

- Dalvik bytecode:

BytecodeViewer(including various decompilers such asProcyon,JD-GUI,CFR,…).Jadx-gui.JEB.

- Native code:

- Disassemblers:

- Dynamic binary instrumentation framework:

Frida.Xposed.

My selection of tools was as such; Frida for performing dynamic analysis, Hexrays for native decompilation and BytecodeViewer (Procyon) for Java decompilation. The Hexrays decompiler was used because its reliable decompilation on ARM code. However, Radare2 plus open-source decompilers can also do a great job.

Extracting the hidden secret

Let’s walk through how we can extract both secrets by reverse-engineering and instrumenting the target application. Note that this needs to be first reversed and then instrumented at the Java and native level. The structure of this post is split in four sections:

- Reverse-engineering Dalvik bytecode.

- Reverse-engineering native code.

- Instrumenting Dalvik bytecode with

Frida. - Instrumenting native code with

Frida.

1. Reverse-engineering Dalvik bytecode (classes.dex)

First of all, several files need to be unpacked from the APK to be reverse engineered later on. For doing that you can use apktool or 7zip. Once the APK is unpacked, two files are very important to follow this post. These files are:

./classes.dexcontains the Dalvik bytecode../lib/arm64-v8a/libfoo.sois a native library that contains ARM64 assembly code. We refer to this when talking about native code during this post (feel free to use the x86/ARM32 code if preferred). As I was running the app in a Nexus5X, the library to reverse engineer was the compiled for the ARM64 architecture.

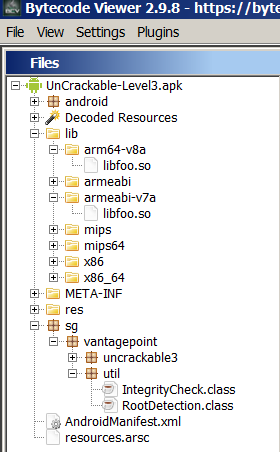

APK packages overview. Source code decompiled from the Dalvik bytecode (classes.dex)

The code snippet of the MainActivity shown below was obtained by decompiling the main class of the UnCrackable app Level3. This has the interesting points to discuss:

- a hardcoded key in the code (

String xorkey = "pizzapizzapizzapizzapizz"). - The loading of the native library

libfoo.soand declaration of two native methods:init()andbaz(), which will be invoked through JNI calls. Notice that one method is initialized with the xorkey. - Variables and class fields to keep track if any tampering has been detected at runtime.

The main activity gets decompiled as follows:

public class MainActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

private static final String TAG = "UnCrackable3";

private CodeCheck check;

Map crc;

static int tampered = 0;

private static final String xorkey = "pizzapizzapizzapizzapizz";

static {

MainActivity.tampered = 0;

System.loadLibrary("foo");

}

public MainActivity() {

super();

}

private native long baz();

private native void init(byte[] xorkey) {

}

//<REDACTED>

}

When the application is launched, the method onCreate() of the main activity gets executed. This method does the following at the Java level:

- Verifies the integrity of the native libraries by calculating the CRC checksum. Note that none cryptography is used to sign the native libraries.

- Initializes the native library and sends the Java secret (

"pizzapizzapizzapizzapizz") towards the native code through JNI calls. - Performs rooting, debugging and tampering detection. If detected any of them, then the application aborts.

The decompiled code is as follows:

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

this.verifyLibs();

this.init("pizzapizzapizzapizzapizz".getBytes());

new AsyncTask() {

protected Object doInBackground(Object[] arg2) {

return this.doInBackground(((Void[])arg2));

}

protected String doInBackground(Void[] params) {

while(!Debug.isDebuggerConnected()) {

SystemClock.sleep(100);

}

return null;

}

protected void onPostExecute(Object arg1) {

this.onPostExecute(((String)arg1));

}

protected void onPostExecute(String msg) {

MainActivity.this.showDialog("Debugger detected!");

System.exit(0);

}

}.execute(new Void[]{null, null, null});

if((RootDetection.checkRoot1()) || (RootDetection.checkRoot2()) || (RootDetection.checkRoot3())

|| (IntegrityCheck.isDebuggable(this.getApplicationContext())) || MainActivity.tampered

!= 0) {

this.showDialog("Rooting or tampering detected.");

}

this.check = new CodeCheck();

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

this.setContentView(0x7F04001B);

}

Once observed the main flow of the application, let’s describe some of the security mechanisms found.

Integrity checks:

As already mentioned above, integrity checks are identified in the function verifyLibs for protecting both the native libraries and Dalvik bytecode. Notice that repackaging the Dalvik bytecode and native code may be still feasible due to the weak CRC checksum used. Just by patching out the function verifyLibs in the Dalvik bytecode and the function baz in the native library, an attacker could bypass all the integrity checks and then continue tampering with the mobile app at will.

The function responsible for verifying libraries gets decompiled as follows:

private void verifyLibs() {

(this.crc = new HashMap<String, Long>()).put("armeabi", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099684)));

this.crc.put("mips", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099689)));

this.crc.put("armeabi-v7a", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099685)));

this.crc.put("arm64-v8a", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099683)));

this.crc.put("mips64", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099690)));

this.crc.put("x86", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099691)));

this.crc.put("x86_64", Long.parseLong(this.getResources().getString(2131099692)));

ZipFile zipFile = null;

Label_0419: {

try {

zipFile = new ZipFile(this.getPackageCodePath());

for (final Map.Entry<String, Long> entry : this.crc.entrySet()) {

final String string = "lib/" + entry.getKey() + "/libfoo.so";

final ZipEntry entry2 = zipFile.getEntry(string);

Log.v("UnCrackable3", "CRC[" + string + "] = " + entry2.getCrc());

if (entry2.getCrc() != entry.getValue()) {

MainActivity.tampered = 31337;

Log.v("UnCrackable3", string + ": Invalid checksum = " + entry2.getCrc() + ", supposed to be " + entry.getValue());

}

}

break Label_0419;

}

catch (IOException ex) {

Log.v("UnCrackable3", "Exception");

System.exit(0);

}

return;

}

final ZipEntry entry3 = zipFile.getEntry("classes.dex");

Log.v("UnCrackable3", "CRC[" + "classes.dex" + "] = " + entry3.getCrc());

if (entry3.getCrc() != this.baz()) {

MainActivity.tampered = 31337;

Log.v("UnCrackable3", "classes.dex" + ": crc = " + entry3.getCrc() + ", supposed to be " + this.baz());

}

}

On top of these integrity checks, we also observe that the class IntegrityCheck also verifies that the application has not been tampered with and thus does not contain the debuggable flag. This class gets decompiled as follows:

package sg.vantagepoint.util;

import android.content.*;

public class IntegrityCheck

{

public static boolean isDebuggable(final Context context) {

return (0x2 & context.getApplicationContext().getApplicationInfo().flags) != 0x0;

}

}

Reading the ADB logs, we can also track which calculations are performed when the app is run. An example of these checks at runtime is as follows:

05-06 16:58:39.353 9623 10651 I ActivityManager: Start proc 15027:sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3/u0a92 for activity sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3/.MainActivity

05-06 16:58:40.096 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/armeabi/libfoo.so] = 1285790320

05-06 16:58:40.096 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/mips/libfoo.so] = 839666376

05-06 16:58:40.096 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/armeabi-v7a/libfoo.so] = 2238279083

05-06 16:58:40.096 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/arm64-v8a/libfoo.so] = 2185392167

05-06 16:58:40.096 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/mips64/libfoo.so] = 2232215089

05-06 16:58:40.096 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/x86_64/libfoo.so] = 1653680883

05-06 16:58:40.097 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[lib/x86/libfoo.so] = 1546037721

05-06 16:58:40.097 15027 15027 V UnCrackable3: CRC[classes.dex] = 2378563664

As we do not want to patch binary code, then we do not investigate more about these checks.

Rooting checks:

The Java package sg.vantagepoint.util has a class called RootDetection that performs up to three checks to detect if the device running the application is potentially rooted. These three checks are mainly:

checkRoot1()that checks the existence of the binarysuin the file system.checkRoot2()that checks the BUILD tag fortest-keys. By default, stock Android ROMs from Google are built with release-keys tags. Iftest-keysare present, this can mean that the Android build on the device is either a developer build or an unofficial Google build.checkRoot2()that checks the existence of dangerous root applications, configuration files and daemons.

The Java code responsible for performing root checks is as follows:

package sg.vantagepoint.util;

import android.os.Build;

import java.io.File;

public class RootDetection {

public RootDetection() {

super();

}

public static boolean checkRoot1() {

boolean bool = false;

String[] array_string = System.getenv("PATH").split(":");

int i = array_string.length;

int i1 = 0;

while(i1 < i) {

if(new File(array_string[i1], "su").exists()) {

bool = true;

}

else {

++i1;

continue;

}

return bool;

}

return bool;

}

public static boolean checkRoot2() {

String string0 = Build.TAGS;

boolean bool = string0 == null || !string0.contains("test-keys") ? false : true;

return bool;

}

public static boolean checkRoot3() {

boolean bool = true;

String[] array_string = new String[]{"/system/app/Superuser.apk", "/system/xbin/daemonsu", "/system/etc/init.d/99SuperSUDaemon",

"/system/bin/.ext/.su", "/system/etc/.has_su_daemon", "/system/etc/.installed_su_daemon",

"/dev/com.koushikdutta.superuser.daemon/"};

int i = array_string.length;

int i1 = 0;

while(true) {

if(i1 >= i) {

return false;

}

else if(!new File(array_string[i1]).exists()) {

++i1;

continue;

}

return bool;

}

return false;

}

}

2. Reverse-engineering native code (libfoo.so)

The Java (Dalvik) and native code are communicated through JNI calls. When the Java code is started, this loads the native code and initializes it with a bunch of bytes containing the Java secret. The native code is not obfuscated excepting the function protecting the secret. Also, it was slightly stripped and not statically compiled. Therefore, we still have many symbols in the binary.

It is important to mention that possibly IDA Pro does not detect the JNI callbacks as functions. For solving so, just go to the exports windows and make a procedure by pressing the key P on the export Java_sg_vantagepoint_uncrackable3_MainActivity_*. After that, you will also need to redefine the method signature by pressing the key Y when located at the function declaration of it. You can define the JNIEnv* objects to get better decompilation as the C-like code shown in this section.

Native constructor:

An ELF binary contains a section called .init_array which holds the pointers to functions that will be executed when the program starts. If we observe what this ARM shared object has in its constructor, then we can see the following function pointer sub_73D0 at offset 0x19cb0: (in IDA Pro uses the shortcut ctrl+s for showing sections)

.init_array:0000000000019CB0 ; ==================================================

.init_array:0000000000019CB0

.init_array:0000000000019CB0 ; Segment type: Pure data

.init_array:0000000000019CB0 AREA .init_array, DATA, ALIGN=3

.init_array:0000000000019CB0 ; ORG 0x19CB0

.init_array:0000000000019CB0 D0 73 00 00 00 00+ DCQ sub_73D0

.init_array:0000000000019CB8 00 00 00 00 00 00+ ALIGN 0x20

.init_array:0000000000019CB8 00 00 ; .init_array ends

.init_array:0000000000019CB8

.fini_array:0000000000019CC0 ; ==================================================

Radare2 also supports the identification of the JNI init methods since very recently. Thanks to @pancake and @alvaro_fe for their quick implementation supporting the JNI entrypoints in radare2. If you are using radare2, just using the command ie will show you the entrypoints. More info about the commits in the references.

The constructor sub_73D0() does the following things:

pthread_create()function creates a new thread executing the code of the function pointermonitor_frida_xposed. This function has been renamed with this name because bothFridaandXposedframeworks are seamless checked in order to avoid hooking.xorkey_nativememory is cleared before being initialized from the Java secret.codecheckvariable is a counter to determine integrity. Later on, it is checked before computing the native secret. Thus, we need to pass this function to have the right value ofcodecheckin the final verification.

The decompiled code of sub_73D0() (renamed to init):

int init()

{

int result; // r0@1

pthread_t newthread; // [sp+10h] [bp-10h]@1

result = pthread_create(&newthread, 0, (void *(*)(void *))monitor_frida_xposed, 0);

byte_9034 = 0;

dword_9030 = 0;

dword_902C = 0;

dword_9028 = 0;

dword_9024 = 0;

dword_9020 = 0;

xorkey_native = 0;

++codecheck;

return result;

}

Native anti-hooking checks:

The function monitor_frida_xposed performs several security checks in order to avoid people instrumenting the application. If we take a peek at the following decompiled code, then we observe that several DBI frameworks are blacklisted. This check is done over and over in an infinite loop and if any DBI framework is detected, then goodbye() function is called and the app crashes.

The function monitor_frida_xposed gets decompiled as follows:

void __fastcall __noreturn monitor_frida_xposed(int a1)

{

FILE *stream; // [sp+2Ch] [bp-214h]@1

char s; // [sp+30h] [bp-210h]@2

while ( 1 )

{

stream = fopen("/proc/self/maps", "r");

if ( !stream )

break;

while ( fgets(&s, 512, stream) )

{

if ( strstr(&s, "frida") || strstr(&s, "xposed") )

{

_android_log_print(2, "UnCrackable3", "Tampering detected! Terminating...");

goodbye();

}

}

fclose(stream);

usleep(500u);

}

_android_log_print(2, "UnCrackable3", "Error opening /proc/self/maps! Terminating...");

goodbye();

}

An example of a tamper detection is shown below where the application aborts with signal SIGABRT(6):

ActivityManager: Start proc 7098:sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3/u0a92 for activity sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3/.MainActivity

UnCrackable3: Tampering detected! Terminating...

libc : Fatal signal 6 (SIGABRT), code -6 in tid 7112 (nt.uncrackable3)

: debuggerd: handling request: pid=7098 uid=10092 gid=10092 tid=7112

DEBUG : *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** *** ***

DEBUG : Build fingerprint: 'google/bullhead/bullhead:7.1.1/N4F26O/3582057:user/release-keys'

DEBUG : Revision: 'rev_1.0'

DEBUG : ABI: 'arm64'

DEBUG : pid: 7098, tid: 7112, name: nt.uncrackable3 >>> sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3 <<<

DEBUG : signal 6 (SIGABRT), code -6 (SI_TKILL), fault addr --------

DEBUG : x0 0000000000000000 x1 0000000000001bc8 x2 0000000000000006 x3 0000000000000003

DEBUG : x4 0000000000000000 x5 0000000000000000 x6 00000074378cc000 x7 0000000000000000

DEBUG : x8 0000000000000083 x9 0000000000000031 x10 00000074323d5c20 x11 0000000000000023

DEBUG : x12 0000000000000018 x13 0000000000000000 x14 0000000000000000 x15 003687eda0f93200

DEBUG : x16 0000007436453ee0 x17 00000074363fdb24 x18 000000006ff29a18 x19 00000074323d64f8

DEBUG : x20 0000000000000006 x21 00000074323d6450 x22 0000000000000000 x23 e9e946d86ea1f14f

DEBUG : x24 00000074323d64d0 x25 00000000000fd000 x26 e9e946d86ea1f14f x27 00000074323de2f8

DEBUG : x28 0000000000000000 x29 00000074323d6140 x30 00000074363faf50

DEBUG : sp 00000074323d6120 pc 00000074363fdb2c pstate 0000000060000000

DEBUG :

DEBUG : backtrace:

DEBUG : #00 pc 000000000004fb2c /system/lib64/libc.so (offset 0x1c000)

DEBUG : #01 pc 000000000004cf4c /system/lib64/libc.so (offset 0x1c000)

On the DBI section, we will walk you through on how to bypass these checks by instrumenting the app in different manners. The best part is that we will use Frida to bypass the anti-frida checks. That’s is priceless! Isn’t it?

Native anti-debugging checks:

The JNI call Java_sg_vantagepoint_uncrackable3_MainActivity_init starts executing the anti_debug function, then copies the xorkey into a global variable and also increments the global counter codecheck to later on detect if the anti-debug checks were done properly. This variable needs to have the value of 2 at the moment of the verification because this would mean that the anti-DBI and -debugging checks were properly completed without errors.

This JNI call gets decompiled as follows:

int *__fastcall Java_sg_vantagepoint_uncrackable3_MainActivity_init(JNIEnv *env, jobject this, char *xorkey)

{

const char *xorkey_jni; // ST18_4@1

int *result; // r0@1

anti_debug();

xorkey_jni = (const char *)_JNIEnv::GetByteArrayElements(env, xorkey, 0);

strncpy((char *)&xorkey_native, xorkey_jni, 24u);

_JNIEnv::ReleaseByteArrayElements(env, xorkey, xorkey_jni, 2);

result = &codecheck;

++codecheck;

return result;

}

Digging into the anti_debug function leads to the piece of code shown just below: (Functions names and variables are manually given by my interpretation)

int anti_debug()

{

__pid_t pid; // [sp+28h] [bp-18h]@2

pthread_t newthread; // [sp+2Ch] [bp-14h]@8

int stat_loc; // [sp+30h] [bp-10h]@3

::pid = fork();

if ( ::pid )

{

pthread_create(&newthread, 0, (void *(*)(void *))monitor_pid, 0);

}

else

{

pid = getppid();

if ( !ptrace(PTRACE_ATTACH, pid, 0, 0) )

{

waitpid(pid, &stat_loc, 0);

ptrace(PTRACE_CONT, pid, 0, 0);

while ( waitpid(pid, &stat_loc, 0) )

{

if ( (stat_loc & 127) != 127 )

exit(0);

ptrace(PTRACE_CONT, pid);

}

}

}

return _stack_chk_guard;

}

The same author of this challenge has written an amazing post explaining how to perform the self-debugging technique. This exploits the fact that only one debugger can attach to a process at any one time. To investigate how this works deeper, please take a peek at his blog cause I will not re-explain the same here.

Effectively, if we run the application with a debugger attached to it then we can see two threads are launched and the application crashes.

bullhead:/ # ps|grep uncrack

u0_a92 7593 563 1633840 76644 SyS_epoll_ 7f99a8fb6c S sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3

u0_a92 7614 7593 1585956 37604 ptrace_sto 7f99b37e3c t sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable3

3. Instrumenting Dalvik bytecode with Frida

At this moment, we need to hide that our phone is rooted. The normal way of bypassing these checks with Frida would have been writing hooks for such functions. Though, an issue came up when placing my hooks on the method onCreate() of the MainActivity. Basically, Frida was not capable of intercepting the method onCreate() at the right moment. Further info can be found at frida-Java issue #29.

However, we can think of different manners to bypass these checks. What about if we take over the control of the system call exit()? Doing so, it would allow us to do not spend time bypassing the Java security mechanisms and after hooking the method exit, we could continue interacting with the application as if no checks had been activated. For that purpose, the following hook can work:

Java.perform(function () {

send("Placing Java hooks...");

var sys = Java.use("java.lang.System");

sys.exit.overload("int").implementation = function(var_0) {

send("java.lang.System.exit(I)V // We avoid exiting the application :)");

};

send("Done Java hooks installed.");

});

Once we place this hook and spawn the application, we are ready to enter the user input. However, the native checks also need to be bypassed.

4. Instrumenting native code with Frida

As seen in the reversing of native code part, there were several libc functions (e.g. strstr) performing some checks for Frida and Xposed. Furthermore, the app was also creating threads to seamless check for debuggers or DBI frameworks being attached to the app. At this stage, we can plan our strategy on how to bypass these checks. A couple of ways came to my mind, either hook strstr or pthread_create. We will walk through in both cases and will show how to place your hooks to achieve the same no matter which hook you choose. Notice that in both cases, the app needs to be spawned due to the fact that Frida injects its agent within the address space of the app and then it gets de-attached. Therefore, anti-debugging checks are not a big issue.

Solution 1: Hooking strstr and disabling the anti-frida checks

Basically, we want to interfere the behavior of this line of decompiled code:

if ( strstr(&s, "frida") || strstr(&s, "xposed") )

{

_android_log_print(2, "UnCrackable3", "Tampering detected! Terminating...");

goodbye();

}

For hooking this libc function, we can write a native hook that checks if the string passed to the function is either Frida or Xposed and returns null pointer as if this string hadn’t been found. In Frida, we can attach native hooks by using Interceptor as shown below: (Uncomment comments in the final hook code if you want to observe the entire behavior)

// char *strstr(const char *haystack, const char *needle);

Interceptor.attach(Module.findExportByName("libc.so", "strstr"), {

onEnter: function (args) {

this.haystack = args[0];

this.needle = args[1];

this.frida = Boolean(0);

haystack = Memory.readUtf8String(this.haystack);

needle = Memory.readUtf8String(this.needle);

if ( haystack.indexOf("frida") != -1 || haystack.indexOf("xposed") != -1 ) {

this.frida = Boolean(1);

}

},

onLeave: function (retval) {

if (this.frida) {

//send("strstr(frida) was patched!! :) " + haystack);

retval.replace(0);

}

return retval;

}

});

The output shown below is after spawning the application with the strstr hook:

[20:15 edu@ubuntu hooks] > python run_usb_spawn.py

pid: 7846

[*] Intercepting ...

[!] Received: [Placing native hooks....]

[!] Received: [arch: arm64]

[!] Received: [Done with native hooks....]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e5d48000-77e6cfb000 r-xp 00000000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e5d48000-77e6cfb000 r-xp 00000000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e6cfc000-77e6d8e000 r--p 00fb3000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e6cfc000-77e6d8e000 r--p 00fb3000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e6d8e000-77e6def000 rw-p 01045000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e6d8e000-77e6def000 rw-p 01045000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77ff497000-77ff567000 r-xp 00000000 fd:00 752212 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-loader-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77ff497000-77ff567000 r-xp 00000000 fd:00 752212 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-loader-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77ff568000-77ff596000 r--p 000d0000 fd:00 752212 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-loader-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77ff568000-77ff596000 r--p 000d0000 fd:00 752212 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-loader-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77ff596000-77ff5f0000 rw-p 000fe000 fd:00 752212 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-loader-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77ff596000-77ff5f0000 rw-p 000fe000 fd:00 752212 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-loader-64.so]

[!] Received: [strstr(frida) was patched!! 77e5d48000-77e6cfb000 r-xp 00000000 fd:00 752205 /data/local/tmp/re.frida.server/frida-agent-64.so]

The strstr hook worked like a charm! We are now undetectable for the application and we can go further in our instrumentation phase. Do you smell what’s the next hook? Later on, we will hook the function that performs the verification by making use of a kind of strncmp with xor.

Solution 2: Replacing the native function pthread_create and disabling the security threads

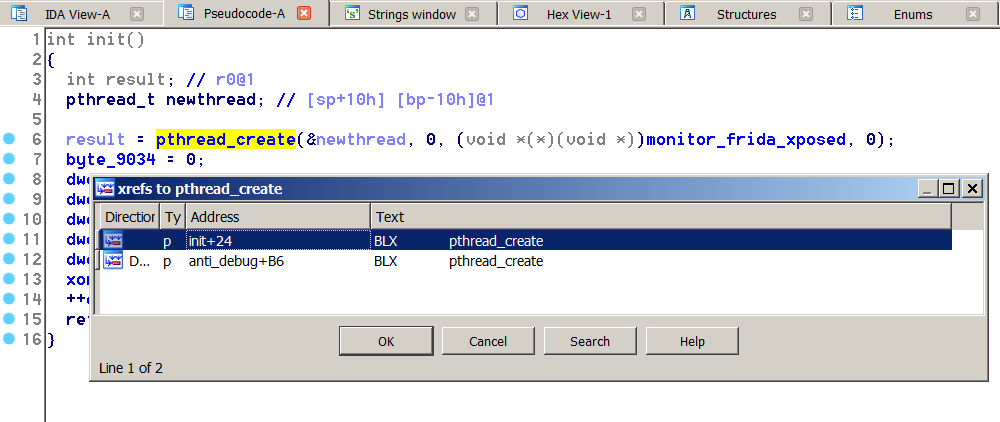

If we look at the cross-references to pthread_create, then we realize that all the references are the callbacks we want to influence to. See more in the next figure:

Cross-references to pthread_create. These xrefs lead to anti-debugging and -instrumentation functions.

It is important to notice that the two threads have something in common. Looking at them, we observe that the first and third arguments are 0 as shown below:

pthread_create(&newthread, 0, (void *(*)(void *))monitor_pid, 0);

pthread_create(&newthread, 0, (void *(*)(void *))monitor_frida_xposed, 0);

In order to avoid these threads, the strategy is as follows:

- Obtain the native pointer from the

libcfunction:pthread_create. - Create a native function with this pointer.

- Define a native callback and overload this method.

- Use

Interceptorwith thereplacemode to inject the replacement. - If we detect that

pthread_createwants to detect us, then we will fake the callback and will always return0simulating thatFridawasn’t in the address space of the process.

The following piece of code is a replacement for the native function pthread_create.

// int pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine) (void *), void *arg);

var p_pthread_create = Module.findExportByName("libc.so", "pthread_create");

var pthread_create = new NativeFunction( p_pthread_create, "int", ["pointer", "pointer", "pointer", "pointer"]);

send("NativeFunction pthread_create() replaced @ " + pthread_create);

Interceptor.replace( p_pthread_create, new NativeCallback(function (ptr0, ptr1, ptr2, ptr3) {

send("pthread_create() overloaded");

var ret = ptr(0);

if (ptr1.isNull() && ptr3.isNull()) {

send("loading fake pthread_create because ptr1 and ptr3 are equal to 0!");

} else {

send("loading real pthread_create()");

ret = pthread_create(ptr0,ptr1,ptr2,ptr3);

}

do_native_hooks_libfoo();

send("ret: " + ret);

}, "int", ["pointer", "pointer", "pointer", "pointer"]));

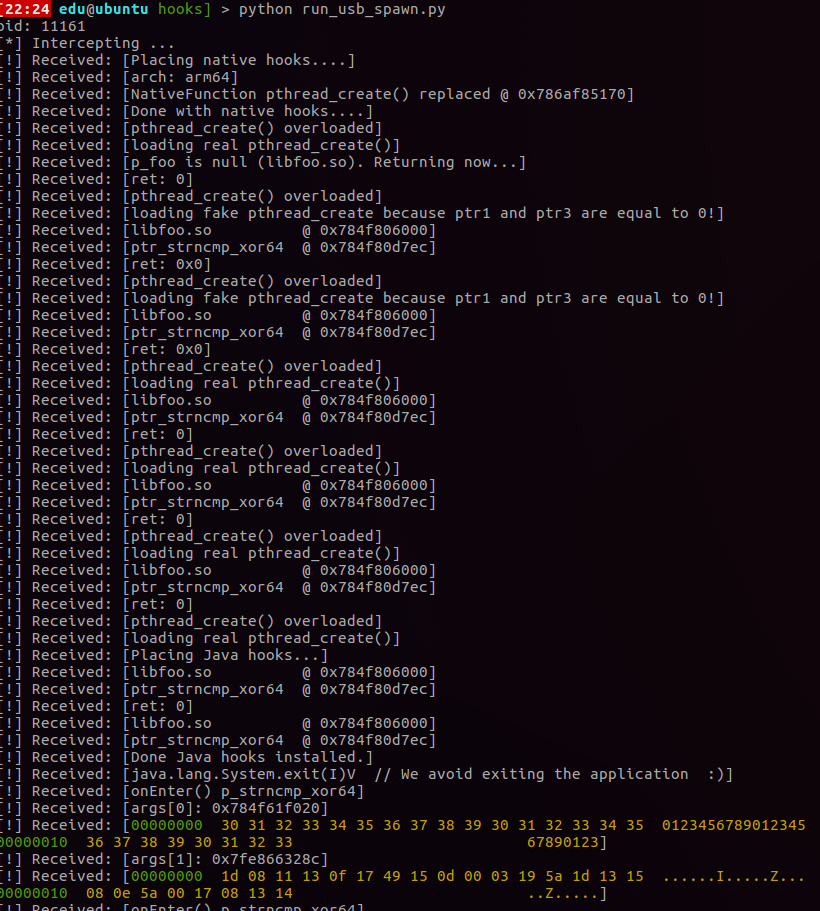

Let’s run our hook and see what’s going on. Note that two native calls to pthread_create were hooked and thus we bypassed the security checks (init and anti_debug functions). Also notice that we want to avoid the calls when first and third arguments are set to 0 and leave working others normal threads in the application.

[20:07 edu@ubuntu hooks] > python run_usb_spawn.py

pid: 11075

[*] Intercepting ...

[!] Received: [Placing native hooks....]

[!] Received: [arch: arm64]

[!] Received: [NativeFunction pthread_create() replaced @ 0x7ef5b63170]

[!] Received: [Done with native hooks....]

[!] Received: [pthread_create() overloaded]

[!] Received: [loading real pthread_create()]

[!] Received: [p_foo is null (libfoo.so). Returning now...]

[!] Received: [ret: 0]

[!] Received: [pthread_create() overloaded]

[!] Received: [loading fake pthread_create because ptr1 and ptr3 are equal to 0!]

[!] Received: [ret: 0x0]

[!] Received: [pthread_create() overloaded]

[!] Received: [loading fake pthread_create because ptr1 and ptr3 are equal to 0!]

[!] Received: [ret: 0x0]

[!] Received: [pthread_create() overloaded]

[!] Received: [loading real pthread_create()]

[!] Received: [ret: 0]

[!] Received: [pthread_create() overloaded]

[!] Received: [loading real pthread_create()]

[!] Received: [ret: 0]

Optionally, if you want to play more with Frida then you might first want to hook the calls to pthread_create and observe the behavior. For doing so, you can start using this hook:

// int pthread_create(pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void *(*start_routine) (void *), void *arg);

var p_pthread_create = Module.findExportByName("libc.so","pthread_create");

Interceptor.attach(ptr(p_pthread_create), {

onEnter: function (args) {

this.thread = args[0];

this.attr = args[1];

this.start_routine = args[2];

this.arg = args[3];

this.fakeRet = Boolean(0);

send("onEnter() pthread_create(" + this.thread.toString() + ", " + this.attr.toString() + ", "

+ this.start_routine.toString() + ", " + this.arg.toString() + ");");

if (parseInt(this.attr) == 0 && parseInt(this.arg) == 0)

this.fakeRet = Boolean(1);

},

onLeave: function (retval) {

send(retval);

send("onLeave() pthread_create");

if (this.fakeRet == 1) {

var fakeRet = ptr(0);

send("pthread_create real ret: " + retval);

send("pthread_create fake ret: " + fakeRet);

return fakeRet;

}

return retval;

}

});

Hooking the secret:

Once arrived here, we are almost ready to go. The next native hook will consist in intercepting the arguments that are compared with the user input. In the following C-like code, we have renamed a function with the name protect_secret. This function generates the secret after a bunch of obfuscated operations. Once generated this secret, it compared with the user input in the function strncmp_with_xor. What about if we hook the parameters entering to this function?

The verification code gets decompiled as follows: (names are given by my interpretation)

bool __fastcall Java_sg_vantagepoint_uncrackable3_CodeCheck_bar(JNIEnv *env, jobject this, jbyte *user_input)

{

bool result; // r0@6

int user_input_native; // [sp+1Ch] [bp-3Ch]@2

bool ret; // [sp+2Fh] [bp-29h]@4

int secret; // [sp+30h] [bp-28h]@1

int v9; // [sp+34h] [bp-24h]@1

int v10; // [sp+38h] [bp-20h]@1

int v11; // [sp+3Ch] [bp-1Ch]@1

int v12; // [sp+40h] [bp-18h]@1

int v13; // [sp+44h] [bp-14h]@1

char v14; // [sp+48h] [bp-10h]@1

int cookie; // [sp+4Ch] [bp-Ch]@6

v14 = 0;

v13 = 0;

v12 = 0;

v11 = 0;

v10 = 0;

v9 = 0;

secret = 0;

ret = codecheck == 2

&& (protect_secret(&secret),

user_input_native = _JNIEnv::GetByteArrayElements(env, user_input, 0),

_JNIEnv::GetArrayLength(env, user_input) == 24)

&& strncmp_with_xor(user_input_native, (int)&secret, (int)&xorkey_native) == 24;

result = ret;

if ( _stack_chk_guard == cookie )

result = ret;

return result;

}

In order to prepare our hook for strncmp_with_xor, we need to obtain certain offsets in the disassemble as well as get the base address of the libc and eventually re-calculate the final pointer at runtime. Attaching to a native pointer can be done by invoking Interceptor. Notice that the hook using the native pointer p_protect_secret is not needed to recover the secret. Thus, you can skip it in your script .

var offset_anti_debug_x64 = 0x000075f0;

var offset_protect_secret64 = 0x0000779c;

var offset_strncmp_xor64 = 0x000077ec;

function do_native_hooks_libfoo(){

var p_foo = Module.findBaseAddress("libfoo.so");

if (!p_foo) {

send("p_foo is null (libfoo.so). Returning now...");

return 0;

}

var p_protect_secret = p_foo.add(offset_protect_secret64);

var p_strncmp_xor64 = p_foo.add(offset_strncmp_xor64);

send("libfoo.so @ " + p_foo.toString());

send("ptr_protect_secret @ " + p_protect_secret.toString());

send("ptr_strncmp_xor64 @ " + p_strncmp_xor64.toString());

Interceptor.attach( p_protect_secret, {

onEnter: function (args) {

send("onEnter() p_protect_secret");

send("args[0]: " + args[0]);

},

onLeave: function (retval) {

send("onLeave() p_protect_secret");

}

});

Interceptor.attach( p_strncmp_xor64, {

onEnter: function (args) {

send("onEnter() p_strncmp_xor64");

send("args[0]: " + args[0]);

send(hexdump(args[0], {

offset: 0,

length: 24,

header: false,

ansi: true

}));

send("args[1]: " + args[1]);

var secret = hexdump(args[1], {

offset: 0,

length: 24,

header: false,

ansi: true

})

send(secret);

},

onLeave: function (retval) {

send("onLeave() p_strncmp_xor64");

send(retval);

}

});

}

This hook gives us the following output when entering the user input 012345678901234567890123. Can you spot the native secret?

Recovering the native secret: Frida rocks!

The following python script generates the user input required to pass the challenge based on the secrets previously recovered:

secret = "1d0811130f1749150d0003195a1d1315080e5a0017081314".decode("hex")

xorkey = "pizzapizzapizzapizzapizz"

def xor_strings(xs, ys):

return "".join(chr(ord(x) ^ ord(y)) for x, y in zip(xs, ys))

user_input = xor_strings(secret,xorkey)

print "The secret is: " + user_input

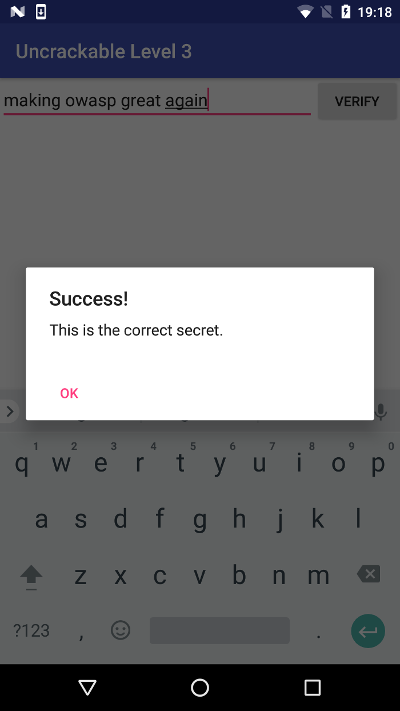

Eventually, we got the secret:

[21:07 edu@ubuntu level3] > python getflag.py

The secret is: making owasp great again

Secret: making owasp great again

The source code of all the hooks can be found at my GitHub page in the androidtrainings repository.

Conclusions:

- None application is

UnCrackable(or 100% secure). Fridarocks! We overcame pretty much all the countermeasures on our way in order to obtain the valid secret. Anti-frida libc-based techniques were bypassed by hooking withFrida. This allowed us to bypass the security checks in different manners and also to debug the application at runtime. Just a comment, but the author ofFrida, @oleavr says that sometimes fixesFridaby instrumenting it withFrida. This is so amazing!- Initial reverse-engineering was required before placing

Fridahooks. - Unlike the Dalvik code, native code can be more tough to deal with.

- Native compilers can optimize too much and therefore introduce unintended bugs or behaviors. Further info in the appendix.

- Bernhard Mueller: Thanks a lot for the challenge! It was so much fun to solve it. Can we expect UnCrackable Level4 to be fully anti-

Frida? Looking forward to it!

That’s all folks! Please comment the way you solved the challenge as well as give me any feedback by posting some comments on the blog. See you around!

Extra: Compiler optimizations.

I had to rewrite the whole write-up after Bernhard Mueller and I detected some problems with the compilation flags in the native library. Just for your information, the two code snippets shown below are the decompilation of the main native function. Please note that all the static operations to hide the final value were optimized and removed by the compiler. Therefore, the native secret is visible and the challenge could be solved just by doing pure static analysis.

Version 1:

The native secret was totally visible just by decompiling the native JNI callback Java_sg_vantagepoint_uncrackable3_CodeCheck_bar:

signed int __fastcall Java_sg_vantagepoint_uncrackable3_CodeCheck_bar(JNIEnv *jni, jobject self, char* user_input)

{

int n; // r0@3

signed int sec_xor_c; // r3@3

int user_input_c; // r6@5

int sec_xor; // [sp+3h] [bp-29h]@2

int v10; // [sp+7h] [bp-25h]@2

int v11; // [sp+Bh] [bp-21h]@2

int v12; // [sp+Fh] [bp-1Dh]@2

int v13; // [sp+13h] [bp-19h]@2

int v14; // [sp+17h] [bp-15h]@2

_android_log_print(2, "UnCrackable3", "bar called\n");

_android_log_print(2, "UnCrackable3", "codecheck: initialized = %d", codecheck);

if ( codecheck != 2 )

return 0;

_aeabi_memclr((char *)&v10 + 2, 19);

sec_xor = 0x1311081D;

v10 = 0x1549170F;

v11 = 0x1903000D;

v12 = 0x15131D5A;

v13 = 0x5A0E08;

v14 = 0x14130817;

((void (__fastcall *)(JNIEnv *, int, _DWORD))(*jni)->GetByteArrayElements)(jni, user_input, 0);

if ( ((int (__fastcall *)(JNIEnv *, int))(*jni)->GetArrayLength)(jni, user_input) != 24 )

return 0;

n = 0;

for ( sec_xor_c = 0x1D; ; sec_xor_c = *((unsigned __int8 *)&sec_xor + n++ + 1) )

{

user_input_c = *(unsigned __int8 *)(user_input + n);

if ( (sec_xor_c | user_input_c) & 0xFF )

goto LABEL_8;

if ( !xorkey[n] )

break;

LOBYTE(sec_xor_c) = 0;

LABEL_8:

if ( user_input_c != (unsigned __int8)(xorkey[n] ^ sec_xor_c) )

return 1;

}

if ( n != 25 )

return 1;

return 0;

}

Version 2:

There was a function, which I renamed to protect_secret, that was performing a bunch of obfuscated operations to thwart attackers from static reverse engineer the code. However, in the prologue the native secret was entirely leaked.

_DWORD *__fastcall protect_secret(_DWORD *secret)

{

int v2; // r4@1

_DWORD *v3; // r0@1

int v4; // r1@2

int v5; // r6@5

_DWORD *v6; // r0@5

// REDACTED

int v17; // r4@21

// REDACTED

v2 = 1103515245 * dword_6004 + 12345;

dword_6004 = 1103515245 * dword_6004 + 12345;

v3 = malloc(8u);

if ( v3 )

{

*v3 = v2 & 0x7FFFFFFF;

v4 = 1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1;

if ( 1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 )

{

v3[1] = *(_DWORD *)(1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 + 4);

*(_DWORD *)(v4 + 4) = v3;

}

else

{

v3[1] = v3;

1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 = (int)v3;

}

}

v5 = 1103515245 * v2 + 12345;

dword_6004 = 1103515245 * v2 + 12345;

v6 = malloc(8u);

if ( v6 )

{

*v6 = v5 & 0x7FFFFFFF;

v7 = 1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1;

if ( 1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 )

{

v6[1] = *(_DWORD *)(1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 + 4);

*(_DWORD *)(v7 + 4) = v6;

}

else

{

v6[1] = v6;

1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 = (int)v6;

}

}

v8 = 1103515245 * v5 + 12345;

dword_6004 = v8;

v9 = malloc(8u);

if ( v9 )

{

*v9 = v8 & 0x7FFFFFFF;

v10 = 1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1;

if ( 1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 )

{

v9[1] = *(_DWORD *)(1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 + 4);

*(_DWORD *)(v10 + 4) = v9;

}

else

{

v9[1] = v9;

1_sub_doit__opaque_list1_1 = (int)v9;

}

}

// REDACTED

if ( result )

{

_aeabi_memclr(secret, 25);

*secret = 0x1311081D;

secret[1] = 0x1549170F;

secret[2] = 0x1903000D;

secret[3] = 0x15131D5A;

secret[4] = 0x5A0E08;

result = (_DWORD *)0x14130817;

secret[5] = 0x14130817;

}

return result;

}

References: